Displaying items by tag: Faculty

The Black experience in ballet, which certainly isn’t singular but is an area of important inquiry, is one Joselli Deans knows well. A dancer for over a decade in Dance Theatre of Harlem under the direction of Arthur Mitchell, and an accomplished dance historian and consultant, she knows this vital history firsthand.

We spoke with Associate Professor Deans, who has recently joined the University of Utah School of Dance, bringing incredible depth of knowledge and experience to our classrooms and studios.

This informal conversation was too rich to condense, so this time, we’re sharing the nearly full transcription with you.

Emeri Fetzer: Let’s start with your early childhood interests and how you discovered dance.

Joselli Deans: I grew up in Brooklyn, New York. I have a Haitian background — my parents, Rene Audain and Anna Cassagnol Audain, are from Haiti. My mother tells me that I stood on my toes all the time. She doesn't know if it was to get out of the crib, or if it was the start of the dancing. There was a lot of music and social dancing at home.

When I was five, my cousin was taking my second cousin (who was a year older than me) to ballet class and said to my mother “Why don't you bring Joselli?” She quit three weeks later, and here I am.

My father had been an actor in Haiti. There was a great influx of Haitian people in New York City in the late 60s because of the political situation with [Hatian politican François Duvalier] Papa Doc. He felt like there needed to be entertainment for them, particularly since many of them were not yet English speaking.

He got a bunch of his acting buddies together from Haiti and started a company, called Theatre Choucoune. I was 7. They did some known plays by Molière, some Haitian plays, and he also wrote his own. Soon, he decided that wasn't enough. He was not a dancer, but he became the executive director to the dance part of the company. He got a choreographer to come in and be the artistic director for the dances.

So, my training started with three folds: I did Haitian dancing in my father’s company, tap, and ballet — so I had the European, the African-based, and the hybrid all between the ages 5 and 7.

Lillian Roberts, who owned the Utica Academy of Music and Dance where I started, asked my mother if I would do Haitian dance in my first recital. One of the women in my father's company taught me a solo, and I did it. My first recital was at the Brooklyn Academy of Music at the age of 5.

Fetzer: How did you get connected with the Dance Theatre of Harlem School?

Deans: My father discovered we had a neighbor named Charles Moore. He was a famous modern dancer, and he lived a block over. He guested at my father's company. As the only child in the company, I used to do the little solo numbers so people could change into the next number.

Charles and his wife, Ella Thompson Moore, saw me dance and thought I was talented. My mother and I ran into Ella on the street (she’s still with us by the way, living in NYC. She’s 92!). She asked what I was doing. At that point, my mother had pulled me out of the dance school because I was spending my entire Saturday there, and it was lots of costumes, three recitals a year, and lots of money.

Ella said, “Well, why don't you take her to Arthur [Mitchell] up at Dance Theatre of Harlem. He just started a school.”

My mother would ride with me on the subway. I started in the summer — I think I went three times a week during that summer. They were still at the Church of the Masters. The following year, they moved up to 466 W 152nd street. I was one of the first to be in the new building.

I was, as he used to say, dependable, consistent, disciplined, and worked hard. I wasn’t as flexible as ballet dancers should be. I was quick. I turned well, I could jump. I learned quickly.

Fetzer: What are some of the favorite moments from your time there?

Deans: Dance Theatre of Harlem started a short-lived (maybe three years) junior company that I was in — so that was quite a thing. And we did some special performances with the company and without them. One of our big performances was at the convention center in Atlantic City where they used to have the Miss America pageant. We performed for the Urban League. Celeste Holm was there, Ruby Dee was there, all these famous people – I have all their autographs in a little book I kept with me.

And then we had a command performance in the dance studio for her Royal Highness Princess Margaret and her husband Antony Armstrong Jones, Earl of Snowdon. He was a photographer, and he took a lot of pictures of the company in the early years.

Another moment was when Miss Tanaquil Le Clercq, who was Balanchine’s last wife, got polio.

Mr. Mitchell was in New York City Ballet with her when she was dancing, and he convinced Mr. Balanchine that she should come and teach at our school. So, she taught in a chair and I used to demonstrate for her in the classes. She and I both spoke French, and she would speak to me in French — I think that empowered her in some ways, because she couldn’t dance anymore. I was very honored to be her demonstrator.

I liked watching the older dancers. I remember sitting on a step there into the studio. We were allowed sometimes to come in and sit there and be very quiet and watch.

I watched incredible dancers.

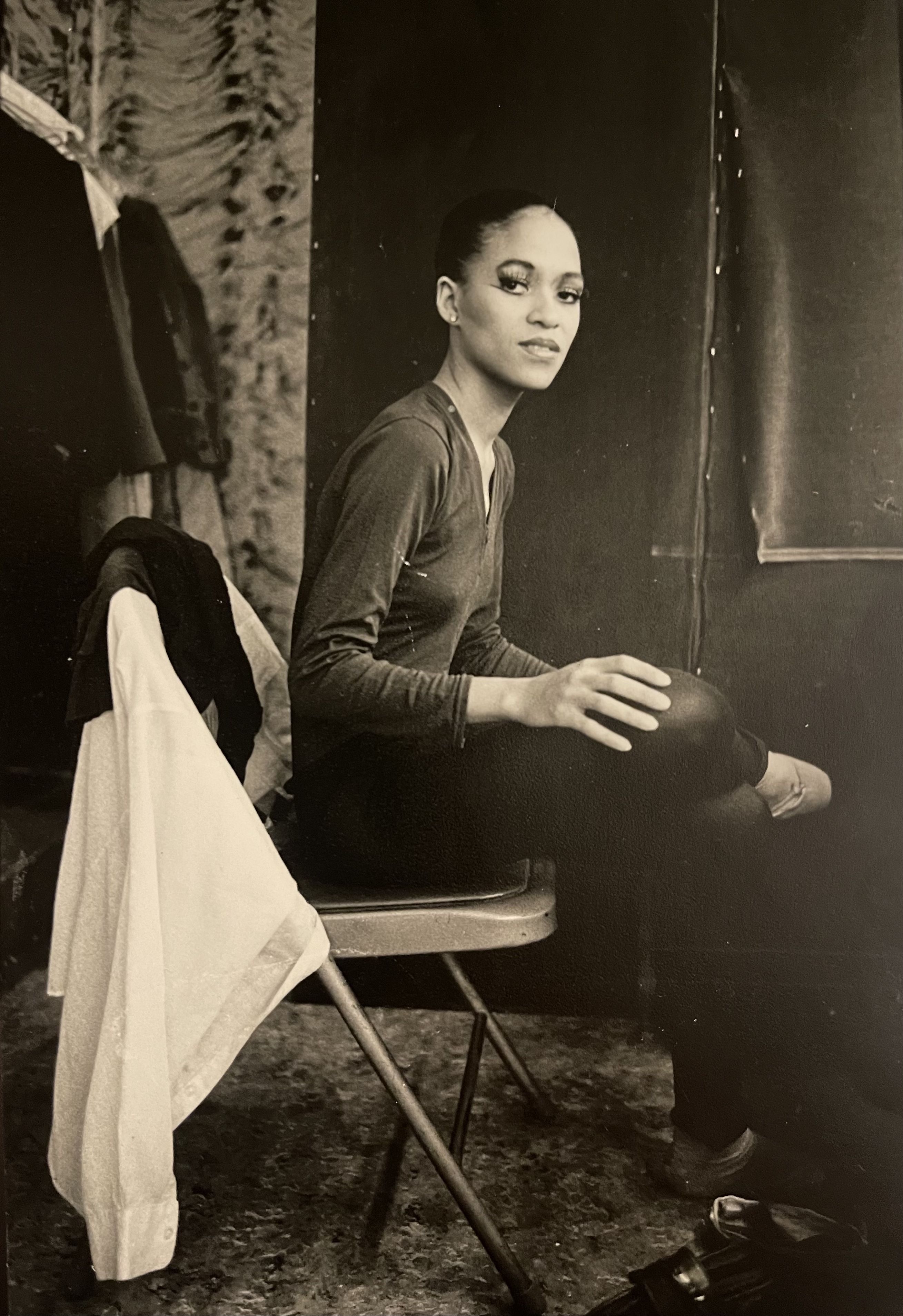

Fetzer: How did you end up transitioning to the company? Dressing room at New York City Center 1983 | photo courtesy Joselli Deans

Dressing room at New York City Center 1983 | photo courtesy Joselli Deans

Deans: I got to the highest level that there was for school students. We had class for two hours a day, every day. I was hiking from high school in Brooklyn to Harlem every day for a two-hour class and back. I consider myself the Forest Gump of Black dance. I just happened to be in the right place at the right time. When Mr. Mitchell was putting together a special class of people, he wanted apprentices.

I walked through the office and he said, “Oh no you can't, because you don't get out of school early enough.”

I said, “I'm a senior. I get out at noon.”

“Can you be here by 1:30?”

I said, “Yes, I can.”

So, in my senior year, I performed in DTH’s first City Center season. I only did two ballets, but that's okay. That's a good start. At the end of that school year in July, the company was going to England and Ireland. I was sort of iffy – the company was an ensemble company, around 30 dancers, but he was starting to expand. I went, but I also helped with the wardrobe as an extra hand.

I was the standby dancer. One night, our lead dancer in “Serenade,” Lorraine Graves, got sick and then somebody had to take her spot. So, I had to go into the corps to replace the girl that was becoming the lead, Karlya Shelton. We didn't use titles, but in ballet terms, she was the highest of the corps. In this dance she did all the extra stuff.

My first performance of “Serenade,” I didn't even get a rehearsal. I got a look through on the video. I knew the steps because I was an understudy, but I had to learn her spacing. It was a lot of pressure. But I got through it. I made a big mistake, but I fixed it. And Mr. Mitchell was very impressed. I said, “I'm sorry I missed the cue.” And he was like, “No, but you fixed it.” I got his attention.

I just worked my way up. I was a corps dancer. I was not particularly fantastic in any way. I was, as he used to say, dependable, consistent, disciplined, and worked hard. I wasn’t as flexible as ballet dancers should be. I was quick. I turned well, I could jump. I learned quickly.

Fetzer: Of course, it is hard to cover all the amazing memories in your 11 years dancing at DTH. But can you share a few highlights?

Deans: DTH was a traveling company — a lot of ballet companies now are not. But DTH was on the road all the time, and so in the 11 years I went to 33 countries and five of the seven continents.

I danced on some of the major stages in the world: the Royal Opera House, the Kennedy Center, the Civic Auditorium where they used to have the Academy Awards before they built the Kodak. Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris…

And this is not necessarily famous, but one of my favorite movies as a little girl was “Sound of Music.” I danced on the stage at the end of the movie. I couldn’t believe I was on the stage where Julie Andrews sang. We danced at an amphitheater that Herod from the Bible built is Israel, the Met in New York, and the 1984 Closing Ceremonies of the Olympics in LA.

Fetzer: Who were some important mentors?

Deans: Well, my father was a great influence. Not so much for my dancing itself, but for understanding history. Our apartment had a long hallway lined with bookshelves. I was a reader when I was a kid. He bought me books all the time, and some about dance. I got this historical sense. And then because DTH was “the first permanent Black ballet company,” I really had a sense of history.

Mr. Mitchell, of course, was a mentor. He pushed me. He saw something in me I didn't see in myself. He said that I would be a great teacher. I must have made an ugly face when he said that. Because back in those days, the adage in dance was, those who can't, teach. I was hurt. He said, “Why is it that when I say you're gonna be a good teacher, you hear I'm saying you are a bad dancer? That’s not what I am saying. What I'm saying is you have a gift, and you need to hone it.”

In 1986, the company was invited to tea at Buckingham Palace, but there were too many of us to go. So, he only took the principal dancers, which made sense. But he or the principal dancers would teach the warmups. With them all gone, who’s going to teach? So, he comes in to teach class that morning and goes, “Okay, I'm going to Buckingham with the principals, Joselli's teaching the warmup tonight.” He didn't ask if I could do it, just did it. So, I started my teaching career with warmup for the Dance Theater of Harlem. I was in awe.

Another influence is a man named William Griffith. We called him Mr. Bill. He was the company teacher from 1980 to 1985. He very much made me the technical teacher that I am. The way I teach from him.

And Kathy Grant, a woman that learned Pilates from [Joseph] Pilates himself. She was DTH's first company manager, and she also taught special exercises, which were based on the Pilates mat work, but she added dance movement. Because I was not flexible, she helped me get the range that I needed to survive as a dancer.

Many of the dancers who got injured would wind up going to her. She would teach me how to do the therapy for them when we would go on the road. Her studio was in Bendel's department store, which was a very swanky place on 57th Street in NYC. She made a deal with my parents. We just paid the store fee and then I would come in on Saturdays, do my workout, but help her when she needed an extra set of hands.

Dance Theatre of Harlem was on the road all the time, and so in the 11 years I went to 33 countries and five of the seven continents.

Fetzer: How did you end up going back to college and on to earn your doctoral degree?

Deans: When I graduated high school and got into the company, I was also going to NYU. There was a program called University Without Walls and I would get credit for my dancing.

I did that for a year and a half. My grades weren’t great, and it was costing a lot of money. I didn't feel like I was getting what I needed out of it. I contemplated quitting.

One of my professors, Sharon Friedman, said, “Look, Joselli, you have an opportunity that dancers would die for. You're dancing with a major company. You're smart, you're hardworking, you're curious. You can always go back to school.” I decided to stop. I went home and I told my father I was quitting, and he hit the roof. It was always a given that I was going to college.

He died in 1986. I left dancing almost in 1990. So, he doesn't know that I went back to school and went as far as I did. I know he would've been really happy.

I am my mother's only child. I was always on the road — that was hard on me, and her.

And then having relationships. I never dated at work. I don't believe in that. If I wanted to get married and have kids, I was getting older. My body was hard to deal with. So I decided to stop. I didn't know what I would do.

But during my career, my spiritual life ignited. I really got interested in how dancing and worship come together. In many other cultures, dancing is based in that. I went and got a degree in theology, and then I was going to go to grad school to put dance and theology together.

I worked at a school with theology and dance, the Institute of Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University. The professors there said, “You won’t get funding to do this kind of work at a graduate level.” I decided that I would go back to school to get a Master of Education so I could teach high school dance in an arts high school. That was the vision. At Temple, they suggested that I do an MFA. I really wanted to learn the strong foundations of pedagogy for dance. While I was doing MEd, the faculty came to me and said, “We want to put you forward for a doctoral degree.” I had never thought of getting a doctoral degree in any form, let alone in dance. But as an African American woman who's getting a free degree where they're paying you to go to school, I thought, “Well, I better do that.”

My father used to always say, “America is the land of opportunity. Don't blow it.”

I got the fellowship. I taught upper-level classes at Temple University as a graduate assistant and as a future faculty fellow. I was at Temple for seven years.

Fetzer: Can you talk a bit about your research and publishing on Black ballet dancers?

Deans: Since I couldn’t do a master’s in dance and theology, I thought maybe I could bring religion and dance together in my doctoral work. Nobody had a background in it in my department. They said, “No, you're a Black ballerina. There's so much to say,” and it's true. There were things happening that were starting to intensify that discussion.

I went to this seminar symposium from Philly to New York called Classic Black — it was about Black ballet dancers before DTH. I had grown up hearing that DTH was the first permanent Black ballet company, and it never dawned on me to ask why “permanent?” I never knew that there were other companies before us. I had heard about certain specific dancers, but not companies.

At this event I heard all the stories about the companies and the individuals. Delores Brown got up and said, “Why can't Black female dancers go into the corps de ballet and work their way up, like everybody else, into principal roles. Why do they have to be principal level just to get in the corps?” My stomach turned over. I decided I would do my dissertation on Black female ballerinas. I selected Janet Collins, who was the first woman to dance with the Metropolitan Opera Ballet. She broke the ceiling. And also Delores Brown, and Raven Wilkinson who danced with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo [disbanded in 1962]. When I went to Ms. Collins, she said no. A woman had just met with her about writing her biography. So, I missed the boat. But my dissertation outlined the other two.

I really had to think about how to talk about racism and ballet. Ballet is the Sacred Cow of Dance in America. I knew I’d have to dot my Is and cross my Ts. I did a lot of research about these companies and dug deeper to do background so I could present my case. That turned out to be 100 pages of my dissertation. It was too long for a chapter. So, it became chapter three and four of my dissertation, and each of these ladies’ orals history became five and six, and then the concluding chapter was seven and the follow up was eight and the whole thing was 400 pages long.

Then things started to happen. I presented a paper at Dancing in the Millennium, which was probably the biggest dance conference in history. I don't know if there's been one since where every dance organization participated. In that paper, I compared reviews of DTH, American Ballet Theatre and New York City Ballet performances of “Swan Lake,” and how critics use different language with our company and other companies. I left all the critics names out of the text, although of course they were cited. I explained that I'm not picking at these critics per se, but the whole system.

One of the critics was in the room. She got defensive and the whole room chimed into my presentation. It was a good feeling.

Later I was invited to be a consultant for the film “The Black Ballerina.” I presented “Blacks in Ballet,” and that's how I started to be known for this topic.

I wound up teaching Catholic high school for seven years, still trying to stay connected to the dance world. Somewhere in the midst of that, Virginia Johnson from the Dance Theater of Harlem asked me to be part of The Equity Project. There were 20 companies that participated. I presented some Blacks in ballet history as part of our four women team equity work with these companies. Christopher Alloways-Ramsey, Sean Carter, and Joselli Deans in "Sleeping Beauty," School of Dance Utah Ballet concert | photo Todd Collins

Christopher Alloways-Ramsey, Sean Carter, and Joselli Deans in "Sleeping Beauty," School of Dance Utah Ballet concert | photo Todd Collins

Fetzer: What impact do you feel like you specifically have in this equity work with organizations?

Deans: I think that I've put forward for them a history that they were unfamiliar with and added context it in a way that they needed to understand it — to understand the idea of Blacks and ballet.

When ballet started to develop itself in America, we were a segregated society. So white people had no idea what black people were doing. But Black people have been studying ballet as long as white people have. It's just nobody knew about it.

And then another comment that I make — particularly back then, not so much now because things have changed and evolved — but a lot of the people that taught Black dancers were Europeans because the white people wouldn't take them on. Europeans would teach them, many times, privately because they couldn't have the Black kids in the school. So they're not only getting European training, they're getting it privately. So the level of some of these dancers, these older dancers, was incredible. And then they opened schools, and they taught people. And then that generation of dancers got to dance in the 40s, 50s and the 60s.

Some went to Europe where they could have a career. Or they were in the Black ballet companies that were short lived in the 50s and the 60s until Mr. Mitchell started DTH in ‘69. I explain that we have documentation that Blacks were studying ballet since 1919.

I don't own Blacks in ballet, but I was one of the individuals who began really delving into it. Now that I'm in this position, in a Research 1 institution where I can do research, I have so many different projects in my brain. I am excited to start.

I think that I've put forward for them a history that they were unfamiliar with and added context it in a way that they needed to understand it — to understand the idea of Blacks and ballet.

Fetzer: What are some challenges that young dancers are facing today?

Deans: The arts have become a business model. It's all about the money. Now, don't get me wrong, we always needed money as artists. But the cost of living for you to dance — you could get two or three roommates and afford to live a decent life, and you can't do that anymore.

Young dancers have to be patient with themselves. They have to realize that although quantity seems to be what's important, both in money and in technique… for the people that really succeed, it's about quality. The quality of your choices, the quality of your dancing, the quality of life that you want to have. That's what gives you longevity. That's what gives you joy and satisfaction.

It's all about the tricks now, and that's not artistry. Artistry will take you into other places, and other levels. I was trained to be an artist. And that's why I can now be a dance historian and all the other things. It’s the level to which I was held –– it was about excellence.

FULL BIO

Joselli Audain Deans, originally from Brooklyn, NY, joined the Dance Theatre of Harlem after receiving most of her training at the company’s school. During her career with DTH she danced numerous roles, including “the accused as a child” in Agnes de Mille’s "Fall River Legend."

A scholar and an artist, she holds a doctorate in Dance Education from Temple University. Her dissertation entitled "Black Ballerinas Dancing on the Edge” documents the lives of Delores Browne and Raven Wilkinson and analyzes how biased ideas and practices impact African American ballet dancers, then and now. She has taught dance technique at Philadanco and several academic institutions including Bryn Mawr College and Temple University; presented her work at scholarly conferences, including at Corps de Ballet International, Association for the Study of African American Life and History, and Collegium for African Diaspora Dance; and her research is published on Arthur Mitchell’s archival collection on Columbia University’s library website curated by Lynn Garafola and in "(Re:) Claiming Ballet" edited by Adesola Akinleye. She has served as a consultant for several institutions and projects including for Dance Theatre of Harlem, American Ballet Theatre, New York City Ballet, School of American Ballet, San Francisco Ballet, Charlotte Ballet, the Dance Oral History Project for New York Public Library, the documentary "Black Ballerina," and was a design and facilitation team member for the Equity Project: Increasing the Presence of Blacks in Ballet.

2022 Utah Art Education Association Awards recognize three University of Utah recipients

Each year, the Utah Arts Education Association awards deserving educators. Recipients of the 2022 UAEA Awards included three members of our U College of Fine Arts community: Beth Krensky, Katie Seastrand, and Sydney Porter Williams.

2022 Higher Education Educator of the Year

Dr. Beth Krensky

Professor, Department of Art & Art History

The theologian Frederick Buechner describes one’s calling as “the place where your deep gladness meets the world’s deep need.” For as far back as I can remember, my deep gladness has come from engaging with others to create art and meaning. Some call this teaching. I call it being part of a community of learners who are willing to inhabit the sometimes uncomfortable space of creativity to remake the world anew. And when I am lucky, time stands still for me and I get lost in the magic of this collaborative grappling we call education. For me, it is always about experimentation. In order to fully inhabit this space, we must be willing to fail. For without the freedom to fail, I believe nothing truly great can emerge. I think this is at the root of the most meaningful forms of education, and teaching from this place is an act of bravery. I believe we must teach as if our lives and the world depended on it. Indeed, they do. I have learned so much with and from my students for so many years as we have courageously collaborated to reinvent the world.

2022 Preservice Art Educator of the Year Award

Sydney Porter Williams

MFA Candidate, Department of Art & Art History

Community-based Art Education

"As a community-based teaching artist, I am inevitably experimenting every day, and have come to embrace the imperfection this brings in my practice. Though I strive for excellence, I have found investigating new methods and materials leads to a more enriching educational experience for all parties. While I enter a classroom with a plan outlined, I am constantly shifting my strategies based on the knowledge and experiences students bring to the table. While I rarely know how a session will develop, I have found that creating this space for experimentation and imperfection allows students to play, leading to a desire to explore and learn more. This desire for learning leads to developed skills, which leads to students believing in their own capabilities. That is my goal: to help students develop agency, a confidence that they can transform the world."

2022 Museum Educator of the Year

Katie Seastrand

Manager of School and Teacher Programs, Utah Museum of Fine Arts

“Using art in classrooms not only provides opportunities for students to learn on their own terms but can also help with stress and social-emotional learning. Students need room to be free and creative, to bring what they want to the paper, canvas, clay, or other medium. Art education is an empowering space and outlet for whatever emotions, anxieties, or experiences that may not easily be expressed through words."

Additionally, Georgiana Simpson, alumna of the U's Master of Arts in Teaching – Fine Arts program, was awarded 2022 High School Art Educator of the Year.

We applaud all of these fantastic educators for their incredible contributions to art teaching in our state!

MAGNIFYING is a series dedicated to showcasing the talent of our students, faculty, and staff to help you learn more about the remarkable individuals within our creative community here at the College of Fine Arts.

Hubbel Palmer, along with his writing partner Chris Bowman, is a recipient of Variety's annual "10 Screenwriters to Watch" award, and recently completed work for Warner Brothers and Legendary Entertainment on the screenplay for a film version of Minecraft, the most popular video game in the world.

The duo has enjoyed the distinction of having two of their movies in the box office top ten simultaneously: Masterminds, a southern-fried crime caper produced by Lorne Michaels and featuring an A-list roster of comic talent (including Zach Galifianakis, Kristen Wiig, Owen Wilson, Kate McKinnon, and Jason Sudeikis), and Middle School: The Worst Years of My Life, a "fun, rebellious romp" (LA Times) that "channels the spirit of John Hughes" (Hollywood Reporter). For the latter film, Bowman and Palmer were hand-picked by the world's bestselling novelist, James Patterson, to bring his passion project to the screen.

Palmer and Bowman were previously staff writers on the Fox animated series Napoleon Dynamite. Their collaboration began a decade ago on an independent feature, American Fork. The film was Bowman's directing debut; Palmer wrote the screenplay and starred as a small-town grocery clerk bitten by the acting bug. After picking up accolades at festivals such as Slamdance and AFI, the pair were selected by the U.S. State Department to travel the world as official cultural diplomats, screening American Fork on five continents.

Palmer, named "Hubbel" by his movie-buff parents after Robert Redford's character in The Way We Were, hails from Salt Lake City, Utah.

What were your interests as a young person? How did film find its way into your life?

I’d say it was my first interest. The first memories I have are of going to the movies. The first movie I remember seeing was called “The Incredible Shrinking Woman” with Lily Tomlin. I just remember being so caught up in the story, and captivated by it. As far as I can remember I just always wanted to do something with making movies or TV as a kid. My parents would try and talk me out of it. They both went to law school. That always felt like a realistic option and I held on to it for a while, but then I dove into film and never looked back.

So did you decide early on you would study film in college?

I had a moment where I considered, “Do I still want to do this film thing or should I do something that really matters?” I wanted to make a contribution. I thought maybe I would pursue Family Studies. There was one semester where I was signed up for two classes. One was intro to family studies, and one was film history. I went to one day of family studies and I was like, “No competition!” I dropped that class and signed up for another film class instead with the same teacher. It was like drinking from a film firehose. It was a compressed semester so I had class every day. I was watching six films a week and just loving it.

Were you making films too?

I made a few films as an undergrad, but I realized I was most interested in writing. I took a class from Paul Larsen (who now teaches at the U). That was the only class where we were looking at feature length films instead of shorts. And I thought, “This is what I really care about—I love short-format stuff, but I want to write movies.” In that class I wrote my first feature length screenplay and it got me so excited about writing that I ended up applying to graduate school in screenwriting, and went on to get my MFA from USC.

We obsess over structure. We spend weeks ironing out the story before we start writing scenes. We try not to be precious about anything--we don’t rest until each scene is as sharp as it can possibly be. Writing can be really hard work but we try and keep it light and fun.

You are also an actor – how does that play in with all this?

That was something I did a lot as a kid. I was in school plays. Any time there was an opportunity for a part that didn’t involve singing, I would try out. I was in several Shakespeare plays--I played Falstaff in “The Merry Wives of Windsor” my senior year of high school, which is sort of “Hamlet for the larger gentleman.” But when I was a freshman in college, I was going back and forth: “Do I want to study acting or film?” And I guess I identified more with the film students.

But you starred in a movie that you also wrote, right?

I had this story that I wanted to tell but I knew I didn’t want to direct it. But I wanted to be on set and involved, and I had written a character that I felt like I could play. I wanted to feel like I was creating the movie along with the director, and it seemed that acting in it was the best way for me to do that.

When you discovered you loved to write, to what kind of stories did you gravitate?

I wrote a sci-fi short in high school that was a variation on “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” – it was about what happens after the invasion. And then the first feature that I wrote in Paul Larsen’s class was an indie comedy in the vein of "Flirting with Disaster."

And what about “American Fork?”

I always had the idea floating around, because in high school I worked as a courtesy clerk at a local grocery store. I worked with a lot of interesting people. One guy in particular really intrigued me. He seemed like he’d been at the store forever and he would stay there long after the rest of us had moved on. So I based the main character on him.

How did you meet Chris Bowman and what makes your partnership last?

We were in the same film program as undergrads. He wrote and directed this short about a guy introducing his new fiancée to his best friend. And it turns out that the fiancée is a sock puppet. I remember thinking that was so weird and hilarious. And so, after I had written "American Fork," I was trying to think of people to direct it and he came to mind. I sent it to him. He liked the script but he had notes. But the thing was, every idea he had was spot on—I could tell it would make the film better. That’s rare. Usually people give you notes that feel like a creative compromise and you have to figure out how to make them work anyway.

So he ended up directing it, and after that we decided we liked working together and we said, “Hey, let’s write something together from the ground up.” And so we did. That led to us getting hired to write for this primetime animated TV show, and from there we had an opportunity to write a studio film, and it just kept snowballing. One thing that helps us work together is that we have very similar tastes. At the time, nearly everyone else in film school was into flashy auteurs. Fincher, the Wachowskis. Chris and I seemed to gravitate more toward the writing behind the movies—voices like John Patrick Shanley, Charlie Kaufman, Steve Tesich and Albert Brooks.

Can you talk a bit about your creative process of working on a screenplay?

We obsess over structure. We spend weeks ironing out the story before we start writing scenes. We try not to be precious about anything--we don’t rest until each scene is as sharp as it can possibly be. Writing can be really hard work but we try and keep it light and fun. If you let the pressure get to you, it only makes the process harder. We’re both perfectionists but in different ways and about different things. We complement each other.

Do you remember any major a-ha moments in your career?

When I was in film school I pictured a life as an indie filmmaker, making tiny film after tiny film. I looked down on my classmates who were writing commercial fare. Well, the truth was that studio writing intimidated me—I just didn’t think I could do it. But an opportunity presented itself and my writing partner and I rose to the occasion. It was an a-ha moment to realize, “Hey, we can do this.”

For students who have a big idea or story to tell, what advice do you have for how to gather the resources or team to make it happen?

I’d say you need to be able to discern between people who talk a big game, and people who can actually get stuff done. I remember trying to pick winners in college – like who was going to succeed. And I was often wrong. Maybe they had an outsized personality, or seemed really entrepreneurial, but they didn’t have ideas. But there were other people, quieter people, who would surprise you with incredible work. Try and find those people.

Where do you gather inspiration?

We always try and think of the movies that we’d like to see that don’t currently exist or that there aren’t enough of. We also have touchstone movies that we watch obsessively. One for me is this Wim Wenders film called “Faraway, So Close!” (That exclamation point is part of the title.) The critics really savaged it at the time, but I think it’s miraculous. I keep a poster of it in my office. I also have a poster of “Housekeeping”, a luminous adaptation of the Marilynne Robinson novel. I’m also inspired when I watch movies with my children, although I’m always sad when they don’t like something I treasure, or they get bored and wander out of the room. Every now and then, though, they have the exact reaction I was hoping for.

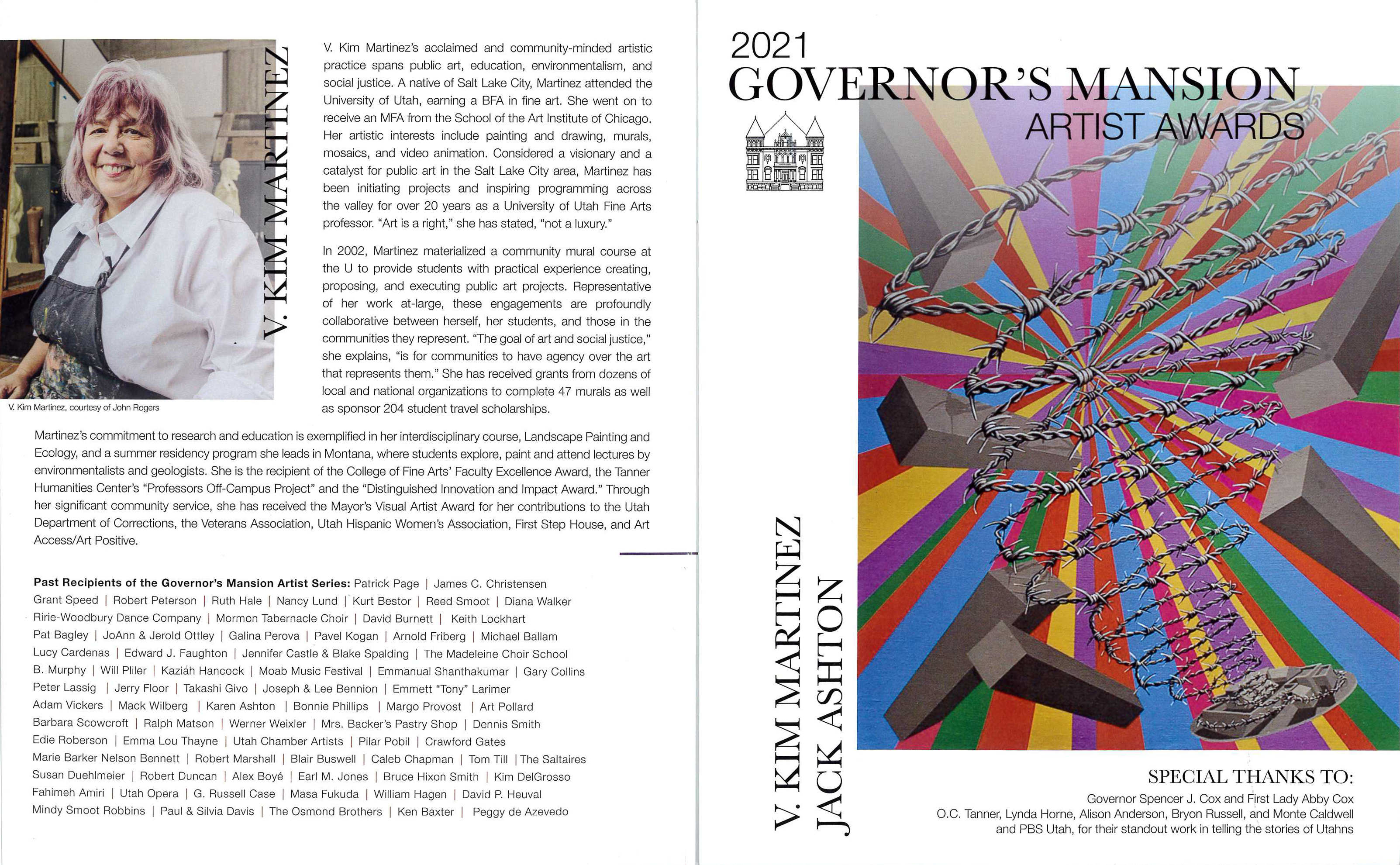

V. Kim Martinez, Department of Art & Art History Chair, wins 2021 Governor's Mansion Artist Award

Each year, Utah’s governor honors three visual artists and three performance artists with the Governor's Mansion Artist Award. The College of Fine Arts is elated to share that V. Kim Martinez, Department of Art & Art History Chair, is one of the selected artists for 2021. Awardees were selected by Governor Spencer Cox and First Lady Abby Cox, from a group of nominees submitted by the Governor’s Mansion Artist Awards Committee.

“Receiving The Utah Governor’s Mansion Visual Artist Award is a reinforcement of my ideals of art as a vehicle for social change. Art has massive power to incite people to find connections to act on the challenges we face by identifying with one another across social, political, gender, and racial lines.”

-V. Kim Martinez

The 2021 award winners include:

- Ta’u Pupu’a, opera tenor

- Elsie Holiday, master Navajo basket weaver.

- Diane Stewart, owner of Modern West Fine Art, benefactor

- V. Kim Martinez, muralist, professor and community activist

- Jack Ashton, violinist, director of Young Artist Chamber Players, educator

- Camille and Alicia Washington, founders of Good Company Theatre

- Fidalis Beuhler, painter, professor

PBS Utah is producing a documentary series about the honored artists to air in the spring of 2022.

Here is a bit more about V. Kim Martinez, shared from the Governor's Mansion Artist Awards program:

MAGNIFYING is a series dedicated to showcasing the talent of our students, faculty, and staff to help you learn more about the remarkable individuals within our creative community here at the College of Fine Arts.

Meekyung MacMurdie is a historian of Islamic art and architecture, with a focus on manuscripts. Her interests include aesthetics and artistic practice, the creation and transmission of knowledge, cultural encounters and exchanges in the medieval world, and historiography. She is currently at work on her first book, which investigates the ontological status and evidentiary stakes of pictures, diagrams, and tables in Arabic scientific and medical works produced in the eleventh through thirteenth centuries. Positioning geometry as a meeting ground between the philosophical and applied arts, the book theorizes the historical significance of facture, while also exploring the mutability of viewers’ reception of visual forms. The project reframes questions about ornament, abstraction, and style in terms of cognition and reasoning in a pivotal period: following the Islamicate reception of late antique forms and preceding early modern articulations of motifs. In addition to research on premodern topics, MacMurdie is collaborating with Jesse Lockard, a historian of post-war architecture, on a project that examines the formative years of the discipline, when—they argue— art history methods were entwined with artisanal tools. The study positions pattern books as a bridge between critical historiography and material object studies, as well as (problematic) early articulations of global art history. MacMurdie received her PhD in art history from the University of Chicago (2020). Before joining the University of Utah for the fall semester in 2021, she is completing the current academic year at the University of Bern as a post-doctoral fellow in the European Research Council-funded "Global Horizons in Pre-Modern Art" research group.

What were your initial career ambitions when you started your undergraduate studies?

I had a pretty firm idea that I wanted to study history of some sort. I was one of those odd children who was always reading lots of history books. It was really a broader interest in narrative, and storytelling, and communication. Then, as I was going into college, I was also interested in political science, and the intersection between history and real-world stakes. I had never taken art history until I got to college, but I did have one history teacher in high school that would bring in images. I specifically remember this famous painting, "Napoleon Crossing the Alps."

As an undergrad, I got to take an art history class and sort of see what it was about – and it was really exciting to me. There was this whole new world of visual material evidence that we can think about when working as a historian. In terms of having a clear career or path, I don’t think I ever really had one actually. I was just following my interests and seeing where it took me. But I felt somehow confident that it would emerge.

Who were some early mentors?

I’ve been extremely lucky during my academic training to have had really excellent mentorship, particularly female mentorship. Even as an undergraduate, I had a professor, Lynda Sexson, whose classes were really engaging and theoretical. I think I took everything she taught. As I progressed through the program, I had opportunities to do research projects with her, too. She had a way of teaching that blended critical thinking with imagination. I think those two things are inseparable, actually. That was a fantastic model.

In grad school, likewise, I had excellent mentors who – I don’t know how they did it – but they intuited what I needed when, helping me find my weaknesses and develop them into strengths.

Curiosity is not just this innate thing. It requires labor – it’s actually a skill. So, I would say train your curiosity, and ask questions.

What drew you to Islamic Art and architecture? How has your area of specialization evolved over time?

When I started graduate school at the University of Wisconsin, I originally thought I was going to work on early modern botanical and scientific prints. I was interested in landscaping as material practice and the production of knowledge and artistic practice. As I was going through the program, I was starting my master’s thesis working on a French botanist traveling to the Middle East recording observations and collecting samples. During that process, I started thinking, “What is the other side? What is the knowledge that is being produced there? What would botany have looked like for someone in the early 18th century Ottoman Empire, for example?” From there, I started looking at things and reading, and I had tons of questions and it didn’t seem like there were many answers. So, I decided to switch programs.

My advisor at Wisconsin, Jill Casid, was incredibly supportive and helped me apply and think about how my study would work. I remember her telling me, after my acceptance came in, that I should go wherever I would be supported to do my best work. That’s something that has really stuck with me. We are getting into this because we are curious and because there is pleasure in it, but we also want to do our best work. That is what led me to Chicago, and to studying there as an Islamicist.

I was going to ask, what goes into choosing a graduate program?

Support in the broadest sense – which means things like opportunities to take languages, funding packages, who your peers and faculty will be. These are people who you will learn a lot from as you go through. Also it means things like, “Is this a city I can live in?”

And how did your goals change once you were in grad school?

I don’t mean to convey that I am not an organized planner. I seem to be in every other aspect of my life except for my academic work. Even as a grad student, I didn’t have a firm idea. Or another way to put it is that the market is so competitive that you are trying to gain as many skills as possible. I certainly tried to diversify myself with different kinds of experiences: museum work, academic teaching. I didn’t think about what the career really meant until very late in the PhD. I did a lot of preparation for all sorts of different paths. I was waiting for things to unfold.

Can you tell us a bit about the projects you are currently working on?

There are a couple big projects that are in the works. The first is a book project on 12th and 13th century Islamic, and particularly Arabic, tables, diagrams, and pictures. And the second is a collaborative project I’m working on with Jesse Lockard, who is a historian currently at the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz. We have been friends and colleagues for a very long time. We were in graduate school together.

I love to collaborate. I love learning from people. Most of my meaningful collaborations have developed over longer periods of time in the sense that they are rooted in longer conversations about different subjects. Jesse teaches architecture and architecture theory. I am an Islamicist. We were both, at the time, teaching courses where we were talking about Owen Jones’ "The Grammar of Ornament," but for very different reasons. We really sort of stumbled into this project that now seems to be about everything and may result in a book. Right now, we are working on an article together.

We have many early attempts at what today we would call a global art history. And, I think you could argue that pattern books are one of these early attempts. But they are rife with colonialism, imperialism, and really problematic categories and ways of thinking cross-culturally. One of the main questions we are really interested in is whether these kinds of problematic archives still have purchase – whether we can use them as an entry way into making a better art history that is more inclusive, more encompassing, that asks better questions. Or, whether those problematic archives should be tossed out and we need to start again. I think that is a question that resonates with scholars in many fields. I think it resonates socially at large. It’s been really interesting in this project with her, thinking about this, because at this point I don’t have an answer to that question.

What about your recent experience at University of Bern?

I spent three years at the University of Bern, particularly as part of a European Research Council-funded project called “Global Horizons.” It was about pre-modern art generally. It was a really exciting opportunity. I worked with brilliant scholars. The project was spearheaded by Beate Fricke. What was so exciting and unique about it was that we had opportunities not just to meet and workshop papers, but also to travel together and to actually go see art. For example, we were in Japan before the pandemic hit with Kris Kersey, who is a fantastic scholar of medieval Japanese art, taking us to Tokyo and Nara. It was an incredibly rich, stimulating, intellectual environment. For me, it’s been a real model for thinking outside the box about how collaboration can work.

What advice do you have for undergraduates studying art history as they figure out what next steps to take?

A couple things. The first is really to be curious. It sounds really cliché but it’s true. Curiosity is not just this innate thing. It requires labor – it’s actually a skill. So I would say train your curiosity, and ask questions.

And then, also, read. Read a lot. Lots of different kinds of things. The craft of the art historian, when it comes down to what is finally produced, is the craft of writing. And reading will help with writing.

What advice do you have about publishing, in particular?

There are a lot of debates about academic publishing now. The fact is, there are a lot of different kinds of venues to publish your work. In many ways it is driven by the work itself – what it is you want to say, and how you want to say it. So, think broadly about what kinds of venues, what kinds of publishers – who do you want to have access?

It can sometimes be really intimidating, and there can be bureaucracies associated with it. So really think about your reader. As a student, your audience is oftentimes your faculty. But, if you expand how you think about your audience and who you want to reach, I think that really helps shape what direction you go with the writing.

MAKING ART WORK is a series that taps into the knowledge and experience of seasoned creatives from our community and beyond for the benefit of our students.

Danny Soulier is an alumnus of the University of Utah School of Music, and is now an Adjunct Assistant Professor in Percussion. He serves as the Principal Timpanist for the Tabernacle Choir and Orchestra at Temple Square (Previously known as “The Mormon Tabernacle Choir”). He originally joined the Tabernacle Choir organization in 2000 and has enjoyed playing both percussion and timpani throughout his tenure there. He has travelled with them on 9 tours which has allowed him the opportunity to perform in many of the great halls in the United States, Canada, and Europe, most notably: Carnegie Hall, the Berlin Philharmonie, and the Musikverein in Vienna, Austria. He received a bachelor's degree in percussion performance from the University of Utah in 2003 and a master's degree in percussion performance from Cleveland State University in 2006.

Besides weekly broadcasts of “Music & the Spoken Word”, a major event associated with performing for the Tabernacle Choir is the annual Christmas Concert that is released each year on PBS. This and other large productions has provided him opportunities to perform with world renowned artists such as Sissel, Bryn Terfel, Andrea Bocelli, Kristin Chenoweth, The King’s Singers, Fredricka von Stade, Evelyn Glennie, Audra MacDonald, Brian Stokes Mitchell, Denyce Graves, David Foster, Angela Lansbury, Nathan Gunn, David Archuleta, Natalie Cole, Richard Stolzman, Santino Fontana, Laura Osnes, Kelli O’Hara, Rolando Villazon, Sutton Foster and Glady's Knight.

He has played with the Utah Symphony since 2002 as an extra percussionist and substitute timpanist. His other professional experiences include performances with the Sun Valley Summer Symphony, New World Symphony, Wheeling Symphony, Ashland Symphony, Ohio Valley Symphony, Midland/Odessa Symphony, Ballet West, and the Utah Chamber Artists. These opportunities have provided him the privilege of performing with artists such as Andrea Bocelli, Garth Brooks, Gladys Knight, and many others. He has studied privately with George Brown, Doug Wolf, Matthew Bassett, Tom Freer, and Tim Adams respectively of the Utah, Buffalo, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh Symphonies. He has performed under the baton of Thierry Fischer, Keith Lockhart, Thomas Ades, Marvin Hamlisch, Erich Kunzel, Alasdair Neale, Pavel Kogan, Craig Jessop, Mack Wilberg, Ryan Murphy and Richard Kaufman.

He directed the University of Utah drumline in 2010 and 2011 and directed the percussion ensemble in 2010. He has been a drumline instructor at several high schools in Utah and Ohio. In 2007, Mr. Soulier began as the founding director of "HYPE"- the Honors Youth Percussion Ensemble for high school students at the University of Utah. HYPE performed annually at the Utah Day of Percussion and “An Evening of Percussion” at the University of Utah.

Mr. Soulier can be heard on recordings with the Utah Symphony and on more than thirty albums produced by the Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square. He is endorsed as a Concert Artist for Pearl/Adams Percussion.

How did you get started in percussion?

Growing up in elementary, I took piano lessons for six or seven years. In fourth and fifth grade, the Utah Symphony does education concerts throughout the state. I remember going to Abravanel Hall in fifth grade. I sat in the balcony, and was able to look down on the orchestra. I remember seeing the timpanist in the back playing a piece with red maracas. I still remember thinking:, “That would be a fun job.”

In middle school, I wanted to play percussion, but they wouldn’t let me because there were already too many percussionists. My mom and dad didn’t want me to play the drums, they thought they’d be too loud. I ended up playing trumpet for two years. Then I got braces (it hurts to play trumpet with braces), so I switched to baritone. But, I kept asking to play drums. Near the end of my ninth-grade year I convince my mom to let me get private lessons on snare drum. In tenth grade, I auditioned for the drum line, and made snare drum, and I never looked back.

Music has a way of connecting people to their emotions. It is important for people to feel that. It can be so inspiring. I took a ton of theory classes while in school, I could diagram and analyze the structure of pieces, but nothing I learned in class really explained where its power came from.

What are some favorite memories or mentors from your time in undergrad at the U?

Doug Wolf was the professor of percussion. I actually took lessons from him in high school, and he was the reason I went to the U. In high school, I loved going up to the percussion ensemble concert. In the fall the drumline always performed at that concert also and I loved that. I had Doug for about a year and a half in college and then I switched over to George Brown, who is the timpanist that I saw playing with red maracas in fifth grade. He became my teacher, mentor, and friend. In many ways he became like a father to me. Doug as well. They are both still close friends.

What were your career ambitions, what did you think your life in music would look like?

When I first went to the U for music, I did it for the scholarship, and I didn’t really think I was good enough to do music professionally. I just wanted to play on the drumline and in the percussion ensemble. I was actually looking for anything else. I thought I would be a hospital CEO or something – just because I wanted to make more money and have a cool title.

I remember one lesson with George, he knew I wasn’t totally committed yet. He started with “Have you ever been passionate about anything?” I responded, “Yeah... music.” He said, “If you don’t go for it, you are going to regret it for the rest of your life.” I asked Doug if he really thought I could make it in music and he said, “I wouldn’t have you here if I didn’t believe it.” Both of them having that confidence in me really helped.

Once I graduated from the U in 2003, I was going to do a master’s degree in percussion performance. I auditioned at Washington, Carnegie Mellon, and Cleveland State. I ended up at Cleveland State – the Cleveland Orchestra is one of the best in the world and I was excited to study in that city with great teachers influenced by the Cleveland Orchestra.

I had some time between graduating from the U and starting my master’s degree. I was newly married, and had a baby. We moved to Texas for seven months before grad school would start in the fall. My father-in-law owns an oil company, and I worked for him and got trained as a Landman during that time. I really enjoyed the work.

When I went to Cleveland State and got my master’s, my goal was to be a principal timpanist for an orchestra – like the New York Phil or Philadephia Orchestra. I took 11 professional auditions. I’ve heard it takes about 40 auditions on average to get your first big job. I didn’t go far enough. It’s so hard, and so time consuming and costs a lot of money to travel to auditions.

After grad school, we moved back to Utah and I was playing for the Utah Symphony about 2 or 3 weeks out of the month. During the grind of practicing so much and performing I realized I wanted to be home with my family on the weekends. I was also teaching a lot of high schools, and private students, and taking gigs every chance I could.

In 2010, I went to Texas for Christmas, and I asked my father-in-law if I could do some work for him on the side, maybe 15 hours a week. I told him I could start in May. By February 1st he had me working 30 hours a week. So, I was back in the oil business and I loved it. In 2012 I moved back to Texas and became the Vice President of the oil company.

I thought I was done with music at that point. After a couple years in Texas, I worked it out so that I could work remotely from Utah. Luckily, when I came back I was able to return to my position with the Tabernacle Choir and started playing for the Utah Symphony again. Now, I feel like I have a really good balance between the oil industry and music.

Do you have advice for students hoping to audition and join professional organizations?

Practice, and take lessons from respectable teachers. Wherever I went, in Texas and Ohio, I was always practicing. Even during the first time I lived in Texas, I went to the high school and met the band director and got permission to practice at the school during my lunchtime.

In grad school, everyone was practicing 7-10 hours a day. So, it takes a ton of practice. But for you to get invited to an audition, you have to have something on your resumé that shows you are playing. I tried to find as many opportunities I could to play with local orchestra’s and took advantage of those chances whenever they would arise.

What is the most rewarding part of directing a drumline?

The most rewarding part is performing – it is what we do all the work for. Halftime at the football games is really exciting. When I was a college kid and a younger instructor, I thought it was really fun to take a 12-hour bus ride through the night to go to a game. What I enjoyed the most as a player and instructor is warming up and playing our drum beats and cadences for a crowd. We would play while the football team warmed up on the sidelines and would perform a little drum show for fans in the south end zone at Rice-Eccles Stadium.

Another big reason I wanted to do percussion is that in middle school I noticed that all the cute girls were sitting by the snare drummers. So, I figured that’s my only chance. It worked out for me because I ended up marrying one of the dancers from the Utah dance team.

What is the most challenging part?

Marching band is so difficult. There is so much music to learn. You have the warm up packet, the pre-game music, two or three different half time shows. Just getting it all in your head, and then add it to moving around on the field? It’s so hard! It requires four hours a day during the season. When it’s done you need five months to recover. But when spring comes again and you hear the drumline warming up, you’re ready to get after it again.

What inspired you to found HYPE at the University of Utah? What has this program meant to you and the students it serves?

The level of kids that were coming to the U was dropping, and there weren’t as many opportunities for them to perform good percussion literature. George and Doug asked me, and encouraged me, to start a high school group to get some kids up to the U and get them involved. My wife helped me come up with the name – Honors Youth Percussion Ensemble. I did it for four years and then some graduate assistants took it on. In the years I did it there were 39 students, and 11 of them ended up attending the U, and a few are now professional players and teachers now. I even play with a few of them in the groups I perform with now. It’s nice when students become colleagues and friends. That’s what George and Doug did for me – Doug recommended me for my first gig with the Utah Symphony.

It’s a cycle. I love performing the most but there is responsibility to teach. I’m happy to be back at the U teaching timpani.

In your opinion, why is music important?

Music has a way of connecting people to their emotions. It is important for people to feel that. It can be so inspiring. I took a ton of theory classes while in school, I could diagram and analyze the structure of pieces, but nothing I learned in class really explained where its power came from. I still don’t know the answer, but its effects are sure. Music has great power to uplift, inspire, excite and even heal.

Even though I now make a majority of my living working in the business world, having my music degrees has really helped me – I didn’t know I would be so good at negotiating deals and managing difficult legal conflicts, Music taught me how to work with people, schedule my time, be organized. It all transferred so well to what I do in oil. Even though it’s just a piece of paper, the things you learn are so valuable. Your education shows that you are committed and dedicated, and can get things done.

"On the Margins of Metaxy" by Sonia and Miriam Albert-Sobrino debuts internationally

Assistant professors in the U Department of Film & Media Arts, Sonia and Miriam Albert-Sobrino (Also Sisters), have debuted their new short film, “On the Margins of Metaxy,” at the Sydney Underground Film Festival in Australia.

In an exclusive group of only 14 short sci-fi films included in the festival, “On the Margins of Metaxy,” is an experimental film that takes audiences to an imaginary world where the boundaries of the normal are broken or bent.

Audiences can stream the film online until September 26th.

But those local to Salt Lake City will have an exciting opportunity to interact with the film in an even more immersive way.

A transmedia installation piece will debut at the Finch Lane Gallery on October 8th and will run until November 19th. Conceptually inspired by the COVID-19 pandemic, the installation immerses audience in a space of transition inviting them to appreciate the healing qualities of the in-between and of thresholds. Catch a brief preview here.

Viewers can also join Sonia and Miriam during the gallery stroll on October 15th at 6p at the Finch Lane Gallery.

In anticipation of the opening of Utah Museum of Fine Art's "Space Maker" on August 21st, we caught up with Department of Art & Art History alumna Nancy Rivera, curator of the exhibition which features 33 artists from the department's faculty.

As UMFA describes, " 'Space Maker' explores the tensions, histories, and myths that shape our experiences of the world. These works, created by a variety of artists in a dynamic range of media, question the bonds between place and identity, reflect on our relationships to the land, and explore the realities that emerge when an imaginary world is created."

Let's take a closer look at the show.

After a year of isolation, what was it like to come back together on a group show of this size?

What was really cool about curating the exhibition was that when I started looking at the work that the artists produced over the last year or so, it was apparent that everyone was impacted and influenced by some of the same issues. Even though their work is created in such different ways – the materials they use are so different – the ideas and concepts that you see throughout the work started to become a narrative that you could connect to and say, “I felt that same way during the pandemic."

It was interesting to see that in some ways, even though we are isolated, those communal experiences are still very present. We all see the things that we experience in a similar manner.

It’s amazing to see that your professors, the people you are learning from and interacting with now in such a big way, are creating such elevated work. It’s something that they should feel inspired by and really proud of – that we have this type of talent within the University of Utah. I really hope students will go and see the show.

How did the "Space Maker" theme emerge and what do those words mean to you?

A lot of the work the artists created very much explored the idea of place – how we relate to it, how we engage with it, how we perceive it. We were forced to be confined in our homes, and were hyper-aware of the things that surround us – and as artists you tend to look at things through a different lens. So they created, in their own way, an interpretation of the spaces they were in, or really thinking about, or even missing and grieving throughout this pandemic. I think it's something you can apply to a lot of the work.

I also wanted to create an idea to view the show in a way that was broad enough that you could find different types of interpretations, because we have 33 artists. The work that they produce is so varied in process and concept. Looking at it through this lens of thinking about space, and their creation of it, is something that everybody can say they think about through their work. Every one of the artists is working with very specific ideas and themes their work is connected to, but in the end, I think there is an overarching idea of a sensibility towards space that connects them all.

What was the logistical process like?

Coordinating all of this is such a big team project, and I could not have done any of this without the UMFA’s amazing staff support. They have this down. All of the artists were invited to submit up to three works, and then I selected the ones I wanted to include in the exhibition. And there were discussions around “how does this fit the theme?”  Nancy Rivera, "Space Maker" curator and U alum

Nancy Rivera, "Space Maker" curator and U alum

When I first started selecting works, I wasn’t thinking about an overall theme. The theme came to me as the work was selected and I was looking through artist statements and titles, and information about each of the works. It was more about selecting the best works aesthetically – the craft and the concept. Everybody is so talented. In the end, the decision of what works were included was very intuitive, selecting work that was representative of each of those artist’s careers but that also spoke to a sensibility for the times that we are living in.

There are some great moments in the exhibition of really unexpected materials. And, also how artists took this moment of being isolated, not being able to enter certain spaces, and took that as an inspiration to create. Sometimes I think that without having had something so profound happen to us, some of those ideas would not have emerged. Much of the work was made in the past year or two, and a majority was created during the pandemic. To see the way that they were inspired to create in that period of time was amazing. These are artists whose work I am really familiar with from my time being their student and even before that. So it's been great to see how their work continues to grow.

What is it like to work with the faculty, now as an alum?

It's such a different dynamic. I still look up to a lot of them, and I am so honored to be able to work with them as a curator, in a way that i never expected. I am grateful for the way that they have embraced my role in the exhibition. It has been great to have one-on-one conversations and brainstorms with them about their work.

And why should students go to "Space Maker?"

It’s amazing to see that your professors, the people you are learning from and interacting with now in such a big way, are creating such elevated work. It’s something that they should feel inspired by and really proud of – that we have this type of talent within the University of Utah. I really hope students will go and see the show.

We can't wait to see the work from these 33 wonderful artists:

Edward Bateman

Simon Blundell

Laurel Caryn

Erika Cespedes

Lewis J. Crawford

Al Denyer

Elizabeth DeWitte

John Erickson

Haynes Goodsell

Joshua Graham

Michael Hirshon

Trishelle Jeffery

Lenka Konopasek

Beth Krensky

Naomi Marine

V. Kim Martinez

Kylie Millward

Martin Novak

Marnie Powers-Torrey

Andrew Rice

Vanessa Romo

Sylvia Ramachandran Skeen

Brian Snapp

Carol Sogard

Paul Stout

Natalie Oliver Strathman

Amy Thompson

Emily Tipps

Maureen O’Hara Ure

Adam Watkins

Moses Williams

Wendy Wischer

Jaclyn Wright

"Space Maker" runs from August 21 to December 5, 2021. For more information, please visit https://umfa.utah.edu/space-maker.

Remember, students get in FREE thanks to Arts Pass!

MAGNIFYING: Kimberly Jew, Department of Theatre

MAGNIFYING is a series dedicated to showcasing the talent of our students, faculty, and staff to help you learn more about the remarkable individuals within our creative community here at the College of Fine Arts.

Kimberly Jew holds a joint appointment in the Departments of Theatre (Associate Professor) and Ethnic Studies. She received her doctorate from New York University, master’s from Georgetown University and bachelor’s from UC Berkeley. She teaches a wide range of topics ranging from Asian American and Pacific Islander studies, to theatre history, dramatic literature, and script analysis. Her expertise lies in modern and contemporary theatre with a research focus on American, Asian American and Pacific Islander theatres.

Dr. Jew has directed numerous university productions and has also composed and edited a collaborative performance project based on local letters to the editor – Lexington’s Letters to the Editor. Furthermore, she has written on a variety of topics, exploring the intersections of feminism, postcolonialism, theatrical experimentation and ethnic identity. Her essays can be found in the journals of Pacific Coast Philology, Pacific Asia Inquiry, MELUS, and in the edited collections, Literary Gestures (Temple University), and Seeking Home (University of Tennessee Press), to name a few.

She is currently co-editor of "Frontiers, a Women Studies Journal," housed at the University of Utah and University of Nebraska. She is editing two special volumes for this journal: “Staging Feminist Futures” and “Black Performance.” One of the highlights of her time at the University of Utah has been serving in a coordinating role for the Diversity Scholars program where she worked with students of color and/or first-generation college goers.

How did you become interested in theatre?

My interest falls into a familiar tale: I saw theatre growing up. My imagination and sensations were awakened at an early age. I remember seeing "Give a Dog a Bone" in London and being fascinated by a strange, frolicking figure of a “man-dog.” I remember seeing "Joe Turner’s Come and Gone" (and that suitcase!), plus many other plays, at the American Conservatory Theatre in San Francisco – as a child. I didn’t always understand the stories in detail, but I felt an emotional fullness and release. I knew that something important about Life was being expressed through these imaginary worlds. To me, it was an act of magic. You take this big, empty, building-sized box, turn down the lights - and you create this fascinating, momentary energy. Then it’s gone. Poof!

I feel really fortunate to have a joint appointment here at the U. I get to engage with a wide range of practices, theories and outcomes, always seeking to find areas of commonality and mutual wisdoms.

How did you choose what to study in your undergraduate studies? What motivated you to go back for your master’s and doctorate degrees?

For better or worse, I’ve always followed my feelings. As soon as I entered college, I sensed that I could live a very full life as a professor. I loved the idea of studying a passion, and sharing that excitement and knowledge with students. I loved hearing my professors talk about their work with one another. I’ve always been a text-based person and so I studied English for my bachelor’s and master’s degrees. I studied Educational Theatre at New York University for my doctorate as it was the perfect combination of dramatic literature and history, with a focus on practical, educational applications. All of this has led to my interest in Ethnic American theatre – where art is generally shaped by an urgent desire to impact the world in tangible terms, especially in regards to exploring diverse identities, cultural histories, racism, and social inequities.

Can you tell us a little about you share your expertise through a joint appointment in Theatre and Ethnic Studies? Why is this combination important to you?

I feel really fortunate to have a joint appointment here at the U. I get to engage with a wide range of practices, theories and outcomes, always seeking to find areas of commonality and mutual wisdoms. I’ve been most intrigued to see how the Theatre & Ethnic Studies majors react when I get to walk across the bridge a bit with them. My Ethnic Studies majors gain a little bit of freedom of form while exploring theatre, and my Theatre majors get to practice and deepen their appreciation of personal perspectives and social contexts. As a side note, I'm very excited to begin my new role this summer as the Program Head for "Theatre Teaching," one of the six programs in the Theatre Department. I will be standing on the broad shoulders of Professor Xan Johnson in serving in this capacity, and I can't wait to begin working with students committed to their love of both Theatre and Teaching.

What’s one moment you consider truly groundbreaking in your professional life?

Speaking of personal perspectives, I am always reminded of a conversation I had while I was teaching at a state school in a depressed part of northwest Pennsylvania. As the school year was ending, I was chatting with a student about her plans for the summer. I was excited for her, assuming she’d enjoy a break from classes. But this is what she said: “Actually, Professor Jew, I’d rather stay in school. All I do for summers is work in the factory. The school year is my break from all of that.” I learned early in my career that we should never assume; always be aware that we might be short-sighted or just plain wrong. Listen to others, pay attention to students’ lives. They are entering stage left while we are slowly exiting stage left.

How did you get involved with "Frontiers", and how does your editorial work inform your teaching?

"Frontiers" has been an amazing collaboration between the divisions of Gender Studies & Ethnic Studies, both housed in the U’s new School for Cultural and Social Transformation. This journal is one of the oldest women’s studies journals in the United States, starting as it did in the Mountain West region in 1975. While working as a co-editor with Professors Wanda Pillow and Darius Bost, I’ve been offered the chance to deeply embrace the feminist practices of collaboration, consensus building, and shared leadership – all important and hot topics in theatre practice and industry standards today!

Leading the cultivation of two special journal volumes that focus on theatre, gender, and race – “Staging Feminist Futures” (February 2021) and “Black Performance” (May 2021) – has been a highlight of my time at the U. What’s more, “Black Performance” features interviews conducted by our very own Theatre students. Interviewees include former U faculty members, Professors Harris Smith and Martine Kei Green Rogers.

Connections between the School of Cultural and Social Transformation and the College of Fine Arts are a rich part of my journey at the U. Currently I am working with a Musical Theatre major, Eva Merrill, on a Transform “Small Research Grant” – this summer we will explore and document what feminism means to young women today.

What things can you be doing right now to set yourself up for success as a professional in the arts?

As a student, how can you start to build relationships in the community?

What resources from the College of Fine Arts should you be sure to take advantage of?

If these questions are on your mind, no matter where you are in your academic journey, this upcoming event is for you.

Going Pro: Set Yourself Up For Life After College

February 5th (Visual Arts) & February 12th (Performing Arts)

2:30 - 4 PM

via Zoom

Presented by the Fine Arts Ambassadors, a group of successful young alumni from your very own College of Fine Arts, two specialized Zoom panels will dive into your burning questions about what happens once you leave college. Hear from selected CFA faculty and alumni about their real-life experiences, and find out how you can get ahead, starting today.

Here's the scoop:

VISUAL ARTS

February 5th (2:30-4 PM)

Panel Host:

Daniel Stergios - BA ‘18 Film Studies, University of Utah

Faculty Panelists:

Henry Becker - Assistant Professor, Department of Art & Art History

Emelie Mahdavian - Producer-In-Residence, Department of Film & Media Arts

with Fine Arts Ambassadors: Mark Macey, Steph Shotorbani, Doug Tolman, Douglas Wilson, Stéphane Glynn, Elyse Jost, and Taylor Mott

PERFORMING ARTS

February 12th (2:30-4 PM)

Panel Host:

Cate Heiner - HBA ‘17 Theatre, HBA ‘17 Writing and Rhetoric Studies, University of Utah

Faculty Panelists:

Alexandra Harbold - Assistant Professor of Directing, Department of Theatre

Satu Hummasti - Associate Director for Undergraduate Programs, School of Dance

Mike Sammons - Assistant Professor & Percussion Area Head, School of Music

with Fine Arts Ambassadors: Jessica Baynes, Tori Holmes Johnson, Elyse Jost, Anne Marie Robson Smock, Matthew Castillo, Kylie Howard, Will Hagen, Martin Alcocer, and Cece Otto