MAGNIFYING is a series dedicated to showcasing the talent of our students, faculty, and staff to help you learn more about the remarkable individuals within our creative community here at the College of Fine Arts.

Paloma Martinez is an award-winning documentary filmmaker and 2019-21 Morales Fellow at the University of Utah Department of Film & Media Arts. Martinez is a graduate of Stanford University's Documentary Film MFA program. She began her storytelling career as a labor organizer in her native Houston, Texas. With her films, she hopes to empower communities and spark dialogue.

In 2018, Paloma was named one of the “25 New Faces of Independent Film” by Filmmaker. Her short documentaries have been broadcast nationally on PBS, featured in The Guardian, The New York Times Op-Docs, and The Atlantic and screened at leading festivals including Hot Docs, AFI Docs, Doc NYC, and San Francisco International Film Festival, winning multiple awards.

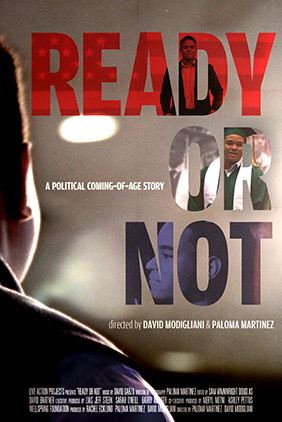

"Crisanto Street" won both the Golden Gate Award for Best Short Documentary and Best Family Film at the San Francisco International Film Festival. "Enforcement Hours" received the Jury Prize for Documentary at Aspen Shortsfest. Her co-directed short "The Shift" was shortlisted for the BAFTA Student Film Awards. This October, her latest film, "Ready or Not," was released — a feature length documentary she co-directed with filmmaker David Modigliani.

How did you get your start in filmmaking?

I had always loved film growing up…It's actually how I understood what it was like to be American, through television and film, growing up with Mexican parents. I had that love for the medium, but it was not something that was available to me when I was growing up in Houston, Texas. I didn't know anybody in the industry, I didn’t even know how you would start doing this. There were no film classes in my public education, and I didn’t take film classes in undergrad.

I started practicing filmmaking in whatever way I could while I was working as a communications director for labor in Texas. It sort of happened to me simultaneously along with my social justice awakening, through this job that I had for many years working with the migrant community all over Texas who were joining together to create unions and better conditions in their workplace. In my capacity as Communications Director I was constantly telling people — who weren't used to telling their stories and weren’t media figures — that their stories were worthy, and training them on how to give those stories to reporters. I had some success and some failures getting the coverage that I thought was really necessary for the issues for people I was working for: migrant workers, janitors and hospital workers...but I couldn't always get the kind of long-form, non-fiction coverage that I was looking for from reporters.

I realized later that I wanted to produce, and that I could tell those stories. That was what led me to start doing my own video pieces, I can't even call them films quite frankly. What I was thinking about was more like documentation, oral history, more traditional kind of documentation, interviewing someone in their home, following someone to work — not thinking about narrative, just thinking, ‘I want to talk to you and I want to get it on camera.’ I decided to go to the MFA program in Documentary Film at Stanford where I was really pushed into the fire very quickly to make a lot of work. And that's how it all began. It's only been 4 years since I've been really making work.

I always tell students that they should be ambitious in their student work, and they should never think that they're going to pour their sweat and tears into something that should sit on a hard drive. If you think that it can go someplace, it can go someplace.

How do you identify the subjects for your films, and how do you gain access to their stories?

We always talk a lot about this when I teach around documentary. When people are asking for access, they always end up negotiating with themselves about how much someone is willing to give. It’s the person asking who ends up thinking “this person is going to say no.” A lot of the time, just you asking is a revealing act to the person who maybe never saw themselves as someone that anybody would be interested in.

When I was approaching folks, these migrant workers who were forming unions and standing up, it wasn’t so much they weren’t willing to speak to me, it was more like, “Why would you want to talk to me? I go to work, I take care of my kids, but I don't really have anything to say.”

Then we would have this conversation about what it took for them to leave everything behind, from Mexico or Honduras or El Salvador, and start a brand-new life, knowing nobody and nothing, not knowing a language — then you understand that this person did an extraordinary thing. I understood that because my parents did the same thing, and they don't think about it as extraordinary. If you're talking about the kinds of films that I tend to gravitate towards it ends up being the kind of person who's like, “ I don't know what I have to say.”  Still from "Crisanto Street"

Still from "Crisanto Street"

I would say a lot of the stories that I've chosen came to me because I was really interested in a person, and also I thought that I could tell the story honorably. So for “Crisanto Street,” for example I knew — for broad strokes — I wanted to make something about the housing crisis in the Bay area where I was living at the time, and sometimes you find your story by knowing what you don't want to do. I’m not an investigative journalist. I'm not someone who tends to do a lot of work about sort-of broad issues. If I am going to tell someone’s story, it’s going to be a hyper-specific story of one person's experience, or one family’s experience that hits a lot of universal themes.

Knowing that that's what I wanted, I just went and dug into the street where I knew that there was this encampment — I lived downtown in the same neighborhood — and I just started to try to meet people. Magically, I met Giovanni’s sister Vanessa. She was playing in the park across the street and she was with her brother. We just started chatting and I asked to meet their mom.

After spending literally just 30 minutes, I could tell that they were incredibly charismatic and great at expressing the joy that I wanted to show when it came to a family life even under dire circumstances. I had to earn their trust and took quite a while, a few months actually, when they started to tell me, “You know we've been on this list, and we actually just got a call and we're moving out in a couple of weeks.” That is when I knew what the film could be... that this could be the plot of the short. It would speak to the issue of housing, the life-changing opportunities that you know having certainty in housing could give to a family. But also, I think it would overturn this clichéd idea of people living in those situations. We associate it with so much negativity so to see a family feeling joy, and feeling love and laughing was kind of a radical prospect.

Can you tell me a little about the making of “Ready or Not,” and the film's subject, Marcel McClinton?

This was a true collaborative effort. I have the privilege of being co-director on this with David Modigliani, who is our Austin-based documentary filmmaker, and has made a lot of other notable work, most recently “Running with Beto,” which was widely distributed and widely shown.

He started the ball rolling. Through his work with “Running with Beto,” he met Marcel, because Marcel was doing all the work on the ground in the Texas grassroots movement against gun violence with other people who had been through gun violence and lost family members. He was right there with them, and was part of the group who was pushing Beto to stand up, and did it successfully. So, David had always just had him in mind because he was such a charismatic person, and decided that he wanted to make a film about his candidacy for City Council. He was seventeen at the time.

David, to his credit, was looking for someone from Houston to help him tell the story, and he contacted me. I was living between Houston and Mexico at the time. I met Marcel, and I was really moved by his overwhelming positivity because I tend to have a pretty negative world view, which dictates my storytelling a lot. So, I thought: I'm interested in being in this headspace for a few months. You know, what is it like for someone who sees every obstacle as an opportunity. As he was explaining his ideas for his candidacy — a total outsider candidate, so young, no experience, new to actual politics — I kept thinking these were all obstacles against him, and he saw them all as opportunities.

Together we worked really hard to get them comfortable with me, and with the crew. What we wanted was intimate access to a family who wouldn't normally be in politics, and how this becomes sort of a family affair. What happens when just some people who want to get in the game because they feel the urgency of the moment — how can this working family do it together, what are going to be the hardships, is it going to get ugly? We thought it was incredibly important to show how many people are prevented from entering politics because it can be so hard. It is all consuming, you need so many resources. And we need more families like Marcel’s in politics.

What does it take to get your work seen, accepted and shared?

I always tell students that they should be ambitious in their student work, and they should never think that they're going to pour their sweat and tears into something that should sit on a hard drive. If you think that it can go someplace, it can go someplace. There are so many avenues online now to get your work seen, even if it's a place that isn't going to pay you for it. This is an incredibly exciting time for non-fiction content. People are looking for quality non-fiction storytelling. There's also a saturation point, but students can take advantage of it, especially when you're young and hungry. I would say that all these places: the Guardian, New York Times, Field of Vision… they are actually looking for people who have access to a story, and in documentary that is the currency. It actually is literally about going to the outlets and explaining what your access is, explaining what your point of view is, showing the work in progress. And yes, sometimes if you don't have the relationships you are cold calling.

For example, my New York Times feature came about because I was lucky enough to have a mentor relationship with somebody who had relationships there. I had cold sent my piece to them and I didn't get a response which happens because they get so many pitches. When my mentor sent it to them, they watched it. I was completely unknown, no clout whatsoever, and they decided to pick it up. That opened a lot of doors for me. I was able to get distribution or other shorts that I had made because people had seen my New York Times short, my Op-Doc. So now I've had the privilege, because of the runs that I've had with my shorts, to be able to be on some screening committees and juries.

I can tell you that if you are submitting something it will get watched, right, so do it. Submit. Submit as many places as you can. I've had really great experiences with film festivals where you have real filmmakers and people who really know about film watching the work. If your work has merit, somebody will highlight it .

What are you working on with students this semester at the U?

Right now, I'm teaching Intro to Documentary Studies, and Advanced Documentary Production. In Advance Documentary Production, we are shepherding along four big projects, their semester-long projects. The class operates a sort of an incubation where we, closely together, shepherd the projects from pre-production to post, and they're going to leave with something ready to go, hopefully to pitch the film festivals and to other mediums and outlets. So, we want to treat it like a professional product pipeline. Every week, students are bringing in footage, giving feedback...then the next week they're bringing in an edit, then a paper cut, then a rough cut, then a fine cut...and we're just fine-tuning and fine-tuning.

I'm very proud of how ambitious they're being. I’m excited at the footage that I've seen so far, because it's good to be ambitious. We have some great equipment that we’re working with — professional equipment that people use in the documentary field and they're getting hands-on experience with it. And at the end of the class they’ll have a film that they co-directed, that they will copyright, and then hopefully it will be out in the world.