By Kate Mattingly

As a researcher who teaches courses in dance histories, dance studies, and dance criticism, I spend a lot of time thinking about how we communicate through our bodies and our words. My dissertation, which I completed in 2017, analyzes how dance criticism not only responds to a performance but also shapes and influences our value systems and priorities. Historically, dance critics have wielded a lot of power: John Martin named the genre “modern dance” and heavily influenced the success of certain choreographers, like Martha Graham, in the 20th century.

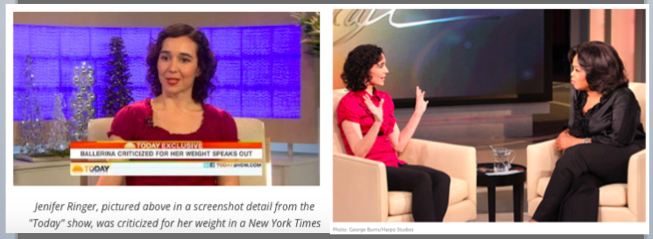

But digital platforms change the status and authority of critics’ words because there are more immediate opportunities to challenge a viewpoint and to use social media platforms to offer different perspectives. A great example of this happened in 2010 when a New York Times critic wrote that Jenifer Ringer, as the Sugar Plum Fairy with New York City Ballet, looked “as if she’d eaten one sugar plum too many.” The outpouring of support for Ringer led to her appearance on The Today Show and Oprah. These interviews are still available online, making the critic's words less definitive.

In my scholarship I analyze how the digital sphere opens spaces for a co-existence of different perspectives, and how this brings attention to artists and ideas that have been misrepresented or completely ignored. Much of my current research focuses on how criticism in the 21st century can challenge the sexisms, racisms, and classisms that have circulated through print critics’ writing. On April 14, I gave a lecture for students and faculty at UCLA on digital dance criticism, and how traces of a project by Amara Tabor-Smith called “House/Full of Black Women,” circulated through photographs Amara posted on Facebook, thereby extending the reach of her processions that happened in Oakland, California. This is an important example of how artists bypass a critic who speaks “for” a project and instead gives the artist access to self-representation and self-definition.

In my dance studies course this semester, when we shifted to an online format, students shared final projects through PowerPoint presentations and then we opened online discussions about the topics. The students’ work was stellar and the online discussions deepened and extended the conversations we had begun earlier in the semester when we were meeting together. One particularly timely project, by Todd Lani ’20, examined social media users who can promote social justice or their own fame. Todd used Matt Bernstein as an example of a social media “activist” who thinks of others and dismantles hate and violence against LGBTQ+ communities. Todd wrote, “Growing up in a smaller rural area, the media (more specifically social media) was the only outlet and opportunity that I had to see any representation of someone like myself.”

During this pandemic, as we find ourselves relying on the digital sphere, we might also be noticing the differences between attending a live performance and watching dancing through a screen. There are undoubtedly things that seem to be missing, like the communal experience of watching a performance with a hundred-plus people, or the feeling of liveness and immediacy as an artist creates the movement in your presence. But there are also advantages: many companies are offering performances to view free of charge, and events that happened in far away places are now visible in our homes.

A student-run group at the University of Utah, the Dance Studies Working Group, took a trip to San Francisco in 2018, supported by funding from a FAF Grant, to see a festival called Unbound and attend a Symposium of guest speakers who included Dwight Rhoden, Virginia Johnson, and Marc Brew. When the company’s current performance season had to be cancelled due to COVID-19, SF Ballet released performances from Unbound online. This Friday students and alumni of the Ballet Program are hosting a zoom conversation, organized by Victoria Holmes Johnson ’19, to discuss the possibilities of online transmission, and also what’s missing in this virtual realm.

We think these conversations are important during this time of uncertainty because we hope that the future of dance, like the future of dance criticism, will be more inclusive and equitable. Artists are known for their imaginations, able to problem-solve and think creatively, and their expertise is invaluable at this moment.

Finally, when people use words like “unprecedented” to describe this pandemic, they are making invisible a lot of people who have not had access to services or movement for years, if not decades. People who are confined and dependent on others due to disabilities could be our teachers. I hope that this moment of "uncertainty" is an opportunity for us to look at our interconnectedness: how do we support and nurture one another? how do we honor our different needs and capacities? I hope we do not return to a world that is about individualism, convenience, and control, but rather one that embraces the interdependencies and indeterminacy of life.

Author Kate Mattingly is an assistant professor in the University of Utah School of Dance.

Assistant professor Kate Mattingly on dance and the digital sphere

Photo: Amara Tabor-Smith's House/Full of Blackwomen Episode: "Now You See Me (Fly)," a ritual procession on the streets of Downtown Oakland against sex trafficking, May 2016. Photo by Robbie Sweeny.

Photo: Amara Tabor-Smith's House/Full of Blackwomen Episode: "Now You See Me (Fly)," a ritual procession on the streets of Downtown Oakland against sex trafficking, May 2016. Photo by Robbie Sweeny.