WRITTEN BY MARINA GOMBERG

PHOTO JIRI STASEK

The town of Klenová, Czech Republic, hosts an international biennial artist symposium every two years perfectly named “Art Dialogue — Interspaces” that in the fall 2018 was the two-week home of Department of Art & Art History MFA candidates, Etsuko Kato and Josh Graham, and their faculty advisor for the trip, adjunct assistant professor, Lenka Konopasek.

The symposium, which welcomes a curated group of around 20 professional artists and students, is appropriately named because of the profound experience it creates uniting people from around the world to make art inspired by their common place.

That place, more specifically, is a grouping of art galleries in and around a 13th century castle nestled on the hill of a rural town outside of Prague. And the inspired dialogue was profound.

Adjunct Assistant Professor Lenka Konopasek’s installation is an exploration into a theme of natural and manmade disasters.

Konopasek, who’s from the Czech Republic, was the connector to this opportunity and in addition to being the faculty mentor, translator, and tour guide, also found time to make work. She created two installations, one of gilded gold emulating light pouring through the window of the castle, and another made from manipulated commercial fabric with feathers and synthetic fibers suspended from a wall representing a collision between nature and people.

For her, the trip was a powerful reminder of humans’ ability to connect and support each other. She, Kato, and Graham all had life-changing experiences making site-specific artwork in the countryside with a house full of (formerly) strangers. The work each of them produced shows just how uniquely they experienced and were inspired by the same place.

For Kato, it was the cobblestone streets made with long, deep stones — the old and timeworn adjacent the those that were newer additions — that captured her attention early in the trip and provided a foundational inspiration for her work. That, and her experience connecting with the other participating artists.

As a Japanese woman influenced by and living in the west, Kato often feels very much between two different cultures. Fielding westerners’ questions about her identity, especially with the complexity of language barriers, had illuminated for her how visual art is her most comfortable mode of communication, not to mention personal introspection.

Through art and translators, Kato built deep connections with some of the women with whom she lived, and took great solace in learning about their families’ similar histories from across the globe during World War II, which had very directly impacted her family. Together, their stories created a fractured but powerful tapestry of that time.

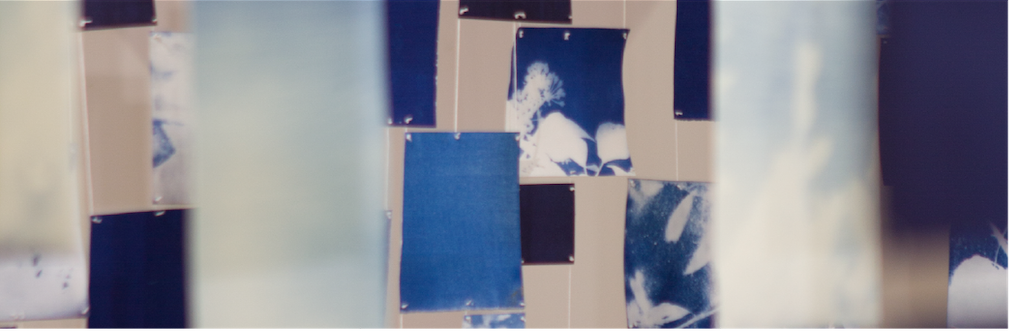

Kato created an installation made from small, layered squares of cyanotype prints, which she made using the few materials she had brought from home combined with the gifted supplies of paper from her new friends. Each piece represented its own unique shadow (cyanotypes are made from a chemical that’s put on paper and then exposed to the sun producing a blue image), some less perfect than others, but together making a shared history of place — not unlike the cobblestone streets and her new set of lifelong friends.

Etsuko Kato’s individual cyanotype prints hung together to create the story of her visit.

Details of Josh Graham’s installed meditative space in a quiet alcove outside the castle.

Graham, on the other hand, found his inspiration in solitude and nature. For the first several days, he walked the land and observed the culture. His intention was to create an interactive work reflective of his communication with the environment.

After collecting raw materials from the factories they visited, Graham, with the help of a local craftsman, welded patinaed metal remnants from a steel mill into a 4’ x 4’ frame, the beginnings of his earthwork.

Graham also gathered needles, sap, and other plant detritus from a ponderosa pine tree he visited regularly on his wanderings. By using material from that particular tree, which is also found across the western United States, he “created a meditative space that sparked questions about communication and connection, and how humans engage with the natural environment.”

He situated the work in a quiet alcove, at the edge of a courtyard within the walls of the historic castle. Once finished, Graham inhabited the space for a day, using it as a way to promote dialogue with visitors to the castle, and encourage conversation about art, performance, and the environment.

“The following day, when I came to check on the piece, I got to witness others interacting with it — walking around it, sitting in it. It was an incredible feeling,” he said, and described how it might pair with a similar piece here in Utah, strengthening the connection between the two locations.

And that was the common thread: human connection through art.

Kato said it best, “With art, there is no right nor wrong answer; it’s something everyone can understand. That is the language — art is language. We can communicate through art.”

Photo Gallery