WRITTEN BY MARINA GOMBERG

PHOTOS SARAH KNIGHT PHOTOGRAPHY

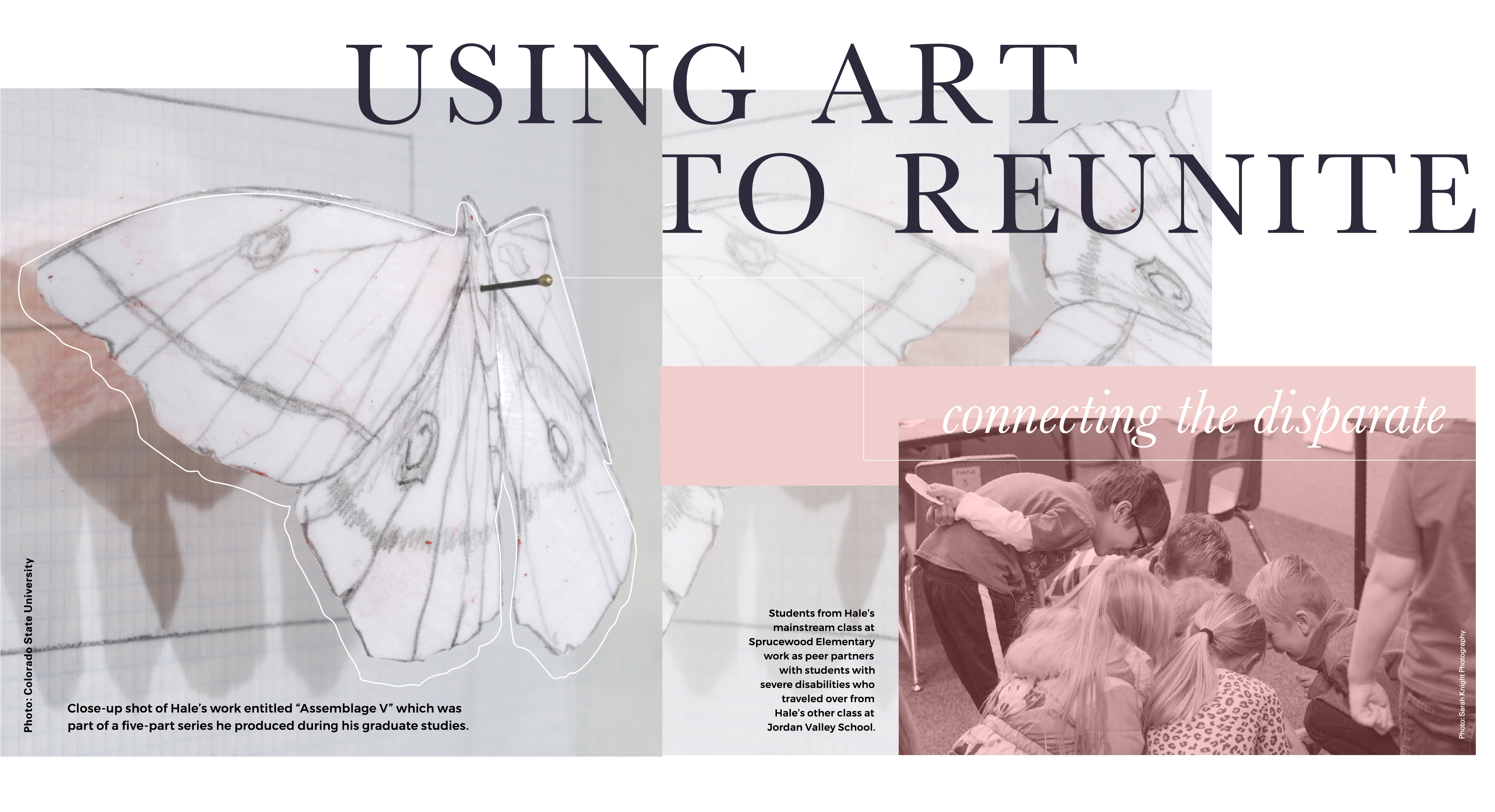

Jon Hale didn’t know art therapy existed when he was he was earning his BFA in painting and drawing here at the University of Utah and supplementing his art practice with sociology and psychology classes. What he did know was that he was interested in the ways cognitive and cultural ideas shaped the content of his work. As he pursued his MFA at Colorado State in drawing and body work, he often employed metaphor in his art — using insects, for example, to illustrate our psychological processes of labeling, naming, and compartmentalizing.

It wouldn’t be for some time that he’d realize that the same tool he used to communicate how we view separateness would be the very thing he would later use to explore kinds of desegregation in schools.

Following his MFA, and during his time at Wayne State in Detroit while he was pursuing his Masters of Education with a concentration in Art Therapy (as well as supplementary class work in art education necessary for teaching certification), he really made the connection about how powerfully art could unite and benefit specific populations of students.

Hale put that new understanding to work on his return to Utah in 2012, when he, as an art teacher, worked with students at a private rehabilitation treatment center and school who had been moved from school to school (and in some cases from state to state) because of mental illness or disciplinary exhaustion that left them and their parents and caregivers at the end of their lines.

“Many of the students in my classrooms were quite disjointed or disconnected from their communities,” he said. “And seeing their successes in the hybrid art-integrated art therapy programs I developed made me wonder if there was a place I could work to possibly prevent that displacement before it occurs.”

Much to his delight, he saw that Utah’s Canyons School District was hiring a Beverley Taylor Sorenson Arts Learning Program (BTSALP) specialist. The Endowed BTSALP in the College of Fine Arts works in partnership with local education agencies to produce collaborative research central to the field of arts and education through the study of integrated approaches to teaching, learning, community engagement, and professional development.

One of the available positions involved working for two schools. The first was Sprucewood Elementary in Sandy, which has both mainstream or typically developing students, along with a population of students who have exhausted existing resources in the district and are at their last step before they have to find other outside resources. The second was Jordan Valley School in Midvale, which houses special education students with severe disabilities, many of whom are there because their cognitive or behavioral abilities are such that it merits having their school services provided in a location away from their typically developing peers. But, some are there because they are medically fragile and require special environments or accommodations.

That’s where Hale wanted to be. So, he applied for the position and got it.

He spent his first year getting his bearings and understanding the new communities and populations of students. And, then he had an idea.

At the end of that year, a fellow BTSALP specialist, Megan Hallett, also a University of Utah alum, presented her work that focused on changing student, staff, and administrators’ perceptions of students in a behavioral unit at Escalante Elementary. The University of Utah’s BTSALP selects top veteran arts specialists annually to work in collaboration with faculty to investigate new knowledge in the field.

“Her presentation, and the others presented that year, opened my eyes to possibilities of doing research in my setting, and specifically, Megan’s work made me want to develop a program that helped to change perceptions of the students in the behavior unit at Sprucewood,” Hale said.

Working with his research team, Dr. John McDonnell, Kelby McIntyre-Martinez, and Kristen Paul, at the University of Utah, he came up with a plan for a project that was specific to both of his populations. While his research was inspired by Hallett’s work, it is different in that his focuses on mainstream students working as peer partners with students with disabilities in the mainstream art classroom.

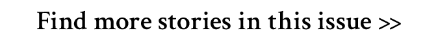

So, after thoughtful planning, Hale and his team picked the student participants through thorough screenings and set out for a six-week experiment. The University of Utah’s BTSALP arranged for the proper resources and transportation from Jordan Valley to Sprucewood, and once every other week, brought the students with disabilities to the mainstream classroom for structured art experiences. A student with disabilities would be paired with a grouping of typically developing students for 45 minutes of art-making.

Almost immediately, Hale witnessed changes in both populations of students. The typically developing students, some of whom might have been reticent at first, became more aware and began incorporating and interacting with their new classmates more and more.

“It’s been interesting to hear those students describe their experiences in our post-interviews,” Hale said. “They reflected on their initial fears, but also talked about how this experience showed them that the students with disabilities are just like them. They are people with preferences and ideas. That feedback is remarkably impactful to hear.”

It was the students with disabilities, though, whose changes were most notable.

“There was one student who vocalized her discomfort the entire first visit,” he said. “And with every subsequent visit, she became more comfortable and more calm. She even began to engage and work intermittently in small bits, which is truly tremendous growth for her. To see her thriving in that environment and interacting was more progress than I could have ever predicted — especially in such a short amount of time.”

Following the six weeks of visits, Hale and his team began assessment of the video footage and field notes taken by the researchers and para-educators. There is still work to be done to understand all the impacts of this project, but Hale is hopeful that their learnings, which they hope to disseminate locally and nationally, might spark interest in other researchers. They continue investigating the benefits of integrating students with cognitive and developmental disabilities into the least restrictive environment with their typically developing peers in efforts to create an environment in which all students can learn from each other.

“By eliminating risk, I wonder if we have inadvertently eliminated the chance to thrive,”

he said. “So, I’m proud to be part of the movement to explore new spaces where all students

can benefit from the diversity of our humanity — and what better way than through the expression of art?”

The Kennedy Center Office of VSA and Accessibility recently featured Hale’s work in a piece entitled, “Peer Partners in the Elementary Art Classroom Lead to Growth for Students With and Without Disabilities”

Photo Gallery